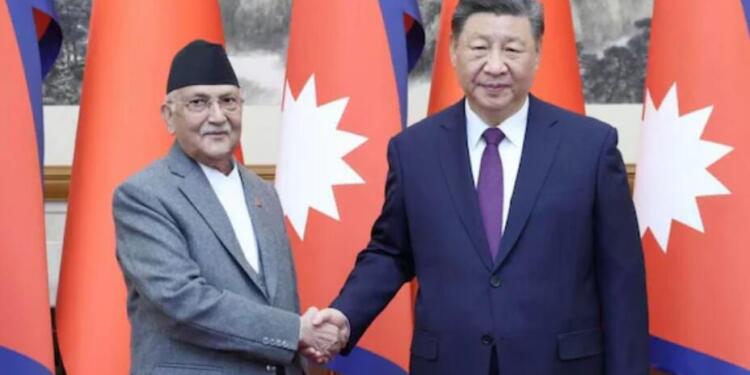

Unlike China, India has no need to flex its girth and size to cow down countries trying to look for alternate trade partners. That’s perhaps what Nepalese Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli must have realised as he returned from Beijing in the first week of December.

Oli decided that China would be his first port of call after assuming office, for the fourth time. He knew he was breaking a tradition of his predecessors visiting India first when embarking on their foreign policy route.

The China visit may be his gamble to look away from India and come closer to China. Given his close ties with the Chinese leadership including President Xi Jinping, it was not an unexpected move.

Also, the meeting between Oli and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the session of the UN General Assembly in September was subsequently misinterpreted to suit Nepal’s needs.

India’s foreign ministry never said Oli got an invite from PM Modi to visit New Delhi. Rather, the word spread that PM Modi told Oli he was planning to visit Nepal soon. Whatever be the truth, information coming from Kathmandu said Nepal took as a “snub” India’s “silence” on Oli’s “invitation” to PM Modi.

However, the truth lies elsewhere. It is not about India. A thought prevailed in Nepal in the past when the 2015 blockade imposed by India crippled Nepal’s economy.

Be that as it may, Oli’s strategy of reducing dependence on India by coming closer to China is pushed by his need for self-survival.

He is not good on popularity charts in Nepal as he is seen not to have done any major works since coming to power a few months ago. His bitter critics call him a Chinese stooge. He is yet to initiate developmental projects as he is perceived to be utilising his time in office to stay in power.

The country’s economy is in dire straits and Oli knows that it needs a strong infusion of finance, preferably Chinese finance.

Nepal’s economy has struggled post-COVID, and the country lacks the resources for Oli to undertake any significant infrastructure or welfare projects on his own.

He needs to initiate at least some BRI projects to reshape his image and present himself as a man of action. However, by unilaterally implementing these projects, he cannot afford to alienate the National Congress, whose support he depends on.

That is the issue. That is why Oli went to Beijing instead of New Delhi.

However, his visit was not really successful. He did not come back with his dreams fulfilled. The Chinese are in a giving mood only when it is beneficial to them; ask any of the myriad small nations now in dire situations after signing BRI projects and ending with huge debts.

There is no new investment okayed by China. Yes, both countries signed the framework agreement on BRI projects without any details and without allaying Nepal’s debt concerns. There were also nine agreements, but they were all previously agreed upon projects. Nepal signed into BRI in 2017 but no project has yet been implemented and things stay there even today.

On the fiscal front too, nothing looks positive for Nepal. Though Chinese tourist inflow has increased, Nepal found to its chagrin that e-payments on Chinese social networking sites and financial fraud cases have been pinching its economy.

Nepal also suffers from a huge trade deficit with China of less than $2 billion a year, while the latter’s investments in Nepal have not seen any upward trajectory.

For long periods the two main border trade routes through Rasuwagadhi-Kerung and Tatopani-Zhangmu are closed either due to the 2015 earthquake, pandemic or landslides.

Previously, Nepal agreed to the Chinese condition that Tibet is an “inalienable” portion of China, and as a follow-up had exerted tremendous pressure on the Tibetan refugees, Kathmandu did not receive anything in reciprocal gesture from China. Same with Nepal agreeing to endorse China’s “anti-secession” law on Taiwan, “three evils” construct and others.

On the other hand, India is a bigger and more consistent trade partner to Nepal. India accounts for two-thirds of Nepal’s international trade while China has a share of just 14%. But China is a bigger two-way creditor, having lent more than $310 million –$30 million more than New Delhi. India has the highest foreign investment in Nepal, pumping in more than $750 million last year.

China has since extended Nepal a loan of $216 million to build an international airport in Pokhara, the second-largest city about 200 km west of Kathmandu, which began operating last year.

But the Chinese-built airport, claimed by Beijing as a symbol of Belt and Road success, has grappled with problems, such as a lack of international flights, due to India’s refusal to let planes use its airspace to reach Pokhara.

Nepal and China watchers say Beijing is trying to exploit the growing rift between Kathmandu and New Delhi and Oli is not helping right the situation. China will use the right as an opportunity if the criticisms of India intensify.

Moreover, Oli’s visit coincides with a thaw in India-China border tensions, marked by recent agreements to cooperate on patrols. While this rapprochement could reduce Kathmandu’s leverage in playing one neighbour against the other, it also opens doors for trilateral cooperation in trade, energy and infrastructure.

Experts argue that a harmonious India-China relationship could ease regional tensions, benefiting smaller nations like Nepal. However, this balancing act is difficult unless Nepal stops positioning China as an alternative to India.