It may be a re-run of the past but with a different ending. As the population of the first world ages, they are looking up to India to import labour. However, unlike in the colonial days, a resurgent India calls the shots today.

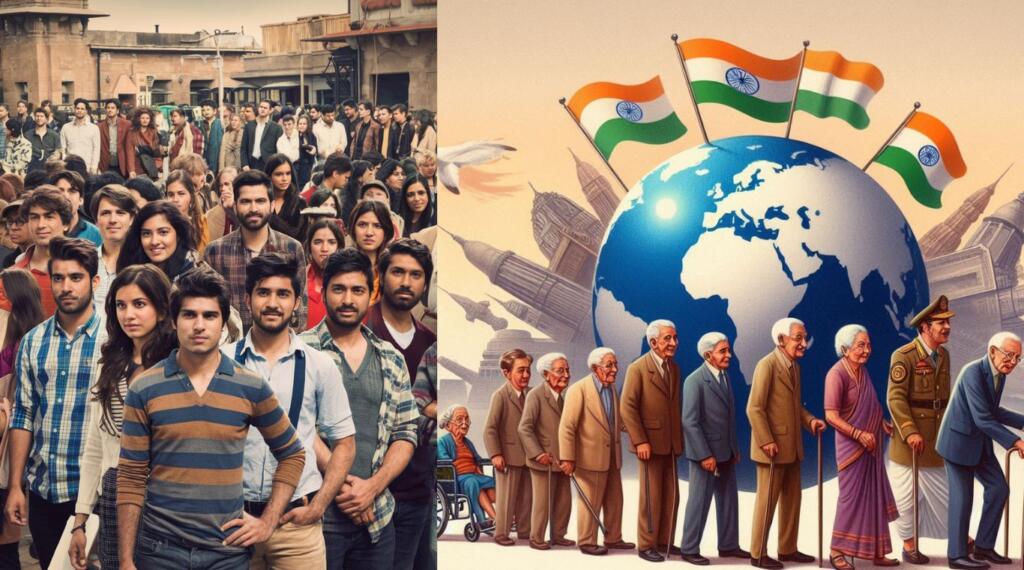

India currently has a demographic bounty. Of its population exceeding 1.4 billion nearly 65 per cent of them are in the working age group of 15-64. More than 27 percent are between the ages of 15 and 24.

It is an enviable youthful demographic profile India projects in the global labour market.

On the other hand, many high-income countries are experiencing rapid demographic shifts characterised by aging populations and declining birth rates.

Some estimates suggest that by 2050, the working-age populations in these countries will have shrunk by more than 92 million, while their elderly populations (65 and older) will grow by over 100 million.

Naturally, this shift creates a critical imbalance. Analyses suggest that working-age individuals are essential for contributing to pension and healthcare systems that support the older generation, thus maintaining financial and social stability.

So, to maintain the current rate of productivity and health and pension costs, the first-world nations will need over 400 million new workers in the next 30 years, a need that domestic workforce mobilisation alone cannot meet.

This is where India can strategically align its labour supply with the demands of advanced economies, ensuring mutual economic growth and integration.

The World Economic Forum says by 2050, there will be 10 billion people on earth, compared to 7.7 billion now—and many of them will be living longer. As a result, the number of elderly people per 100 working-age people will nearly triple—from 20 in 1980, to 58 in 2060.

For example, the working-age population in Germany is projected to decline by 10 million by 2050, while the elderly population will rise significantly. Similar trends are observed in Japan, Italy, and other developed nations.

Japan holds the title for having the oldest population, with a third of its citizens already over the age of 65. By 2030, the country’s workforce is expected to fall by 8 million—leading to a major potential labour shortage.

In another example, while South Korea currently boasts a younger-than-average population, it will age rapidly and end up with the highest old-to-young ratio among developed countries.

Globally, the working-age population will see a 10% decrease by 2060. It will fall the most drastically by 35 percent or more in Greece, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. On the other end of the scale, it will increase by more than 20 percent in Australia, Mexico, and Israel.

Several countries have already approached India, looking for importing Indian labour. Japan was among the first to have a formal agreement. A few thousand Indian agricultural labourers, well versed in agricultural methods and trained in basic knowledge of Japanese life and language, were sent to Japan on a contract. They are able to save money to send home and most expect to get their contracts renewed.

In 2021, Indian foreign secretary Harsh Shringla and Japan’s ambassador Satoshi Suzuki signed a memorandum of cooperation to boost the mobility of skilled Indian workers in 14 fields, including nursing, industrial machinery, shipbuilding, aviation, agriculture and the food services industry.

The memorandum has a framework for partnership for specified skilled workers (SSWs), whereby Indian workers in 14 categories who meet skill requirements and pass Japanese language tests will be eligible for employment on a contractual basis.

More than 38,000 Indians currently live in Japan. In recent years, the composition of the Indian community has changed with the arrival of more professionals, including in IT, engineering, management, finance, and scientific research.

Israel is another country which has labour import agreements already in place between 2023 and 2026 and is eager to extend them even when it is in currently in conflict with Palestine and Hezbollah.

Both countries decided on labour migration in May 2023. Around 10,000 labourers subsequently landed in Israel. The country wants an equal number to migrate again. The National Skill Development Corporation has invited applications from 10,000 potential migrants for various job categories in Israel.

There were media reports early this October of a cabinet minister in Uttar Pradesh, Anil Rajbhar announcing at a government function that the government was proposing to send skilled Indian labourers to Scotland, Japan and the Gulf.

However, for India to take advantage of the demographic demand and stay on top of the skills migration process, several challenges need to be first met. Labour perceptions in India have to change. Developing vocational skill sets must become a priority. Restrictive immigration policies and anti-immigrant sentiments must be removed in the first world countries.

Immigration processes in these countries need to be simplified for quality migration of skilled labour from India. The host countries must also have in place integration programs to help the labourers settle down smoothly.

A research paper by the Observer Research Foundation recently said India has to professionally push its advantage in the global labour market through some strategic measures. It lists three of them.

One, is the need to identify high-demand sectors in advanced nations that face acute labour shortages, such as healthcare, information technology, education, and manufacturing.

Two, analyse the economic implications of integrating Indian labour into these sectors using labour market frameworks, including assessing the productivity of Indian workers and the overall global financial impact.

Lastly, enhance labour mobility by identifying enabling conditions for global labour migration from India involves reducing labour mobility transaction costs and ensuring the smooth reintegration of returning workers into the Indian labour market.