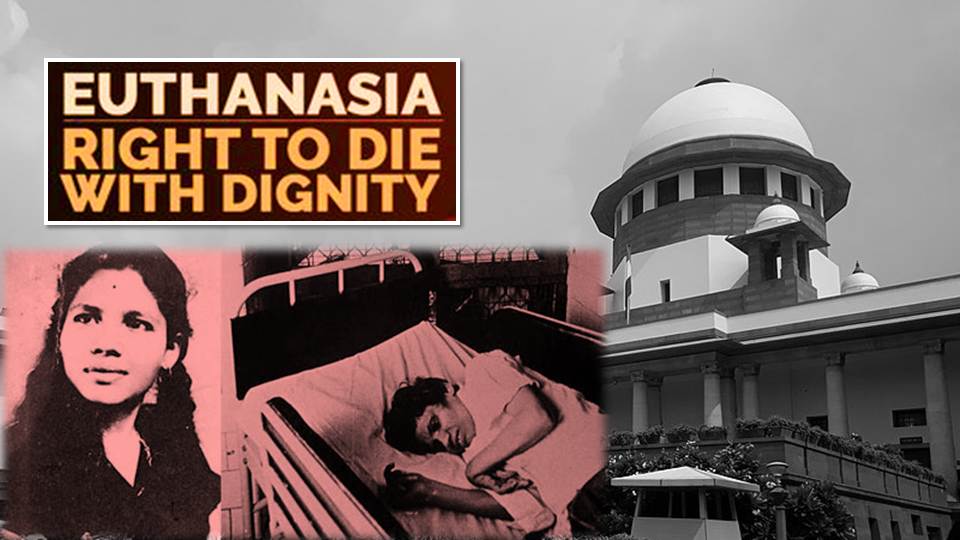

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union of India case: Our legal system explicitly provides for the Right to life to all its citizens. However, the matter regarding the “Right to Die” has been subjected to various interpretations from time to time. At the heart of this debate lies the question pertaining to the legality of passive euthanasia.

Passive euthanasia was considered to be one of the most perplexing issues that courts and legislatures all over the world have pondered over. Often synonymous with “mercy killing,” the practise aims to end the prolonged torment and pain of a patient through the willful withdrawal of life support.

The landmark judgement of Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs. Union of India marked the onset of the debate over passive euthanasia. The Bench, comprising Justice Markandey Katju, and Justice Gyan Sudha Misra, clarified that the right to die with dignity includes the right to end the pain and suffering of a person in a vegetative state.

The division bench of the Apex Court thereby gave one of the most progressive judgments by providing legal sanctity to the practise of passive euthanasia. However, in light of the 13th-century British doctrine of Parens Patriae, the court established certain guidelines for the implementation of law.

Also read: 2018, Joseph Shine vs. Union of India: The assault over institution of marriage

Factual Background: Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug Case

The Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union of India case arose after one Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug, a staff nurse employed in King Edward Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, was attacked by one of the hospital’s sweepers. In an attempt to rape her, he choked and strangled her with a dog chain. The attack caused severe damage to the cortex of the brain and cut off oxygen supply to her brain, leaving her blind, deaf, and paralysed for life.

She was in a vegetative state for the next 42 years, while the convict roamed freely after undergoing seven years of imprisonment. From the day of the incident, i.e., 27 November, 1973, to the day she died on May 18, 2015, Aruna could not move her hands or legs, could not talk, or perform the basic functions of a human being.

Dictum of the Court

The Hon’able Court drew the distinction between active and passive euthanasia. The court was of the view that “Active euthanasia” refers to the positive and deliberate termination of one’s life by injecting and administering lethal substances. The practice is considered a crime as it is an infringement of Section 302 and Section 304 of the Indian Penal Code.

Moreover, the court even clarified that physician-assisted suicide is also an offence under the purview of Section 309 of the IPC. In contrast, passive euthanasia refers to the withdrawal of life-support systems or medical treatment from a patient in an exceptional situation.

The court pointed out that the foremost distinction between active and passive euthanasia is that in “active” euthanasia, something is deliberately done to end life, whereas in “passive” euthanasia, something is not done, i.e., withdrawal of the life support system.

Therefore, the Supreme Court elucidates detailed procedures and guidelines for granting passive euthanasia in the “rarest of rare circumstances” while rejecting the plea made by the petitioner. The apex court bestowed the right under the doctrine of Parens Patriae to the High Court under Article 226. The High Court is therefore entitled to make decisions regarding the withdrawal of the life support system.

The court reiterated that, on receipt of such an application, a bench must be constituted by the Chief Justice of the High Court.

Further, the application should be referred to a committee of three reputed doctors. On their recommendation after a thorough examination of the patient, the state and the patient’s family members are to be provided with a notice issued by the bench. The Apex Court elaborated on the threats posed by the misuse of the law before bestowing the High Court with the responsibility to overcome any such menace.

Social scrutiny of the judgement

The legalisation of passive euthanasia is considered to be against our national ethos and morals. Taking someone’s life is considered a crime. However, in certain cases, the right to life becomes more of a bane, and it becomes mandatory to take deliberate actions to put an end to one’s life.

Nonetheless, in our society, public opinion is divided on the issue of passive euthanasia. On one side of the spectrum, life is considered to be preserved at all costs, as human life is of paramount importance.

Thereby, passive euthanasia dilutes the sanctity of human life and is against the order of nature. On the other hand, the constitutional right to die with dignity falls under the purview of the right to life. Therefore, no person can be forced to live in anguish and pain.

Thereby, furnishing every person with the right to die with dignity, in order to end their suffering and pain. That is to say, the law on passive euthanasia was originally against the idea of mercy killing. However, the historical judgement in the “Aruna Shanbaug case” brought about a tectonic shift in the legal landscape on the issue.

Support TFI:

Support us to strengthen the ‘Right’ ideology of cultural nationalism by purchasing the best quality garments from TFI-STORE.COM

Also Watch:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6DlkkVaTOuI