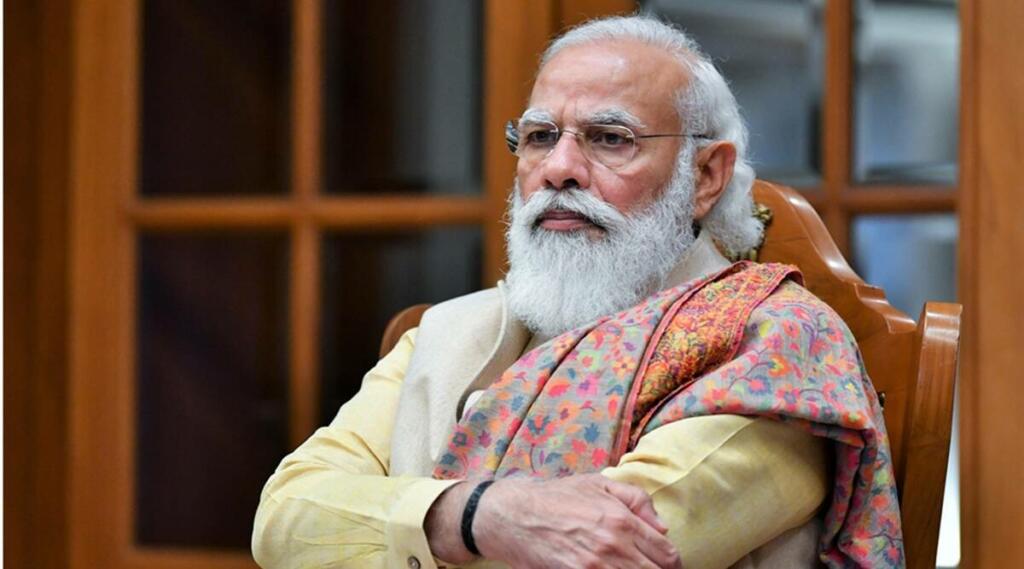

Prime Minister Modi is a man of reforms and big infrastructure projects. He is looking to clear all bottlenecks in the execution and completion of infrastructure projects.

The Prime Minister has reportedly asked Cabinet Secretary Rajiv Gauba to lead an exercise for identifying decisions of various courts and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) that are causing delays in infrastructure projects, prepare a list of all such delayed projects and the loss incurred to the exchequer. So, what could be the purpose behind the latest exercise?

Clearing bottlenecks:

Right now there is no official word as to what the government plans to do after completing the exercise, but it is the top-level intervention by the Prime Minister and the involvement of the Law Ministry indicates a coordinated legal approach to clear bottlenecks in a plethora of such infrastructure projects.

Appointment reforms around the corner?

The Modi government has been looking to reform the appointments system in India’s judicial setup ever since it came to power in 2014. In the subordinate courts, the government wants to formulate an all-India judicial services cadre in order to streamline the process of recruitment and appointments.

As for the higher judiciary, the Parliament had enacted the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act and the 99th Constitution Amendment in 2014. The NJAC was supposed to replace the collegium system in higher judiciary appointments. The NJAC was contemplated as a six-member body comprising the CJI, two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Union law minister and two eminent members from the society

However, the Supreme Court had struck down both of them as unconstitutional a year later. It was held that the NJAC Act and the 99th Amendment impinged on the independence of the judiciary.

Still, the then Union Finance Minister, late Arun Jaitley had said, “The judgment has upheld the primacy of one basic structure — independence of the judiciary — but diminished five other basic structures of the Constitution, namely, parliamentary democracy, an elected government, the council of ministers, an elected Prime Minister and the elected leader of the opposition.”

Criticism of the collegium system:

It is not as if the collegium system is accepted as foolproof by the Indian judiciary. Even in its NJAC verdict, the apex court had admitted that all is not well with the collegium system of “judges appointing judges”.

Justice J.S. Khehar who has presided over the five-judge Bench in the NJAC case had said, “Help us improve and better the system. You see the mind is a wonderful instrument. The variance of opinions when different minds and interests meet or collide is wonderful.”

The collegium system has been a subject of criticism in the recent past. Retired Supreme Court Judge, Justice Ruma Pal, for example, said, “The mystique of the process, the small base from which the selections were made and the secrecy and confidentiality ensured that the process may on occasions, make wrong appointments and, worse still, lend itself to nepotism.”

Five-member NJAC?

Presently, the High Courts are functioning at around 50% of their sanctioned strength, whereas 213 names against 410 vacancies are pending with the government/Supreme Court collegium. Once, names are cleared by the collegium, the executive can theoretically sit over appointments as long as it wants. This leads to pending judicial vacancies in the higher judiciary.

So, how should the Modi government resolve the issue of delays in higher judiciary appointments? One way is to bring a new NJAC Act with a 3:2 composition, that is, an NJAC with three judges and two executive members (the Law Minister and an eminent personality nominated by the executive). The NJAC Act, 2014 was struck down because it destroyed the primacy of the judiciary in judicial appointments. However, a five-member NJAC might survive a Constitutional challenge and harmonize the appointments process.

What about the NGT?

The issue with the National Green Tribunal (NGT) is more procedural and technical. It is essentially related to the culture of frivolous petitions and so-called activist lawyers trying to put obstacles in infrastructure projects by masquerading as climate activists.

The NGT Act explicitly allows a period of 30 days for an affected party to challenge an environmental clearance to a given project. Further, the NGT can condone a delay of another 60 days’ delay if “sufficient cause” is proved. In 2020, as many as 22 appeals were dismissed by the NGT. In 11 cases, the appellants had not approached the Tribunal in time.

Now, for how long can projects stay delayed? It is imperative that the legislature dilutes the excessive leverage given to petitioners under the NGT Act.

Other reforms that the government can contemplate are better regulation of litigation and advocacy, especially due to the tendency of the left-liberal cabal to delay infrastructure projects and to file Mala fide PILs that actually advance political interest in the garb of public interest.