The Ram Janmbhoomi dispute having been resolved in November last year opened the floodgates for Hindus to reclaim their innumerable other temples, which have historically borne the brunt of Islamic invasions and destructive supremacy of foreign rulers. The biggest impediment to such reclamation of lost heritage, however, is the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991. However, now a PIL has been filed before the Supreme Court seeking to render the said Act null and void.

The public interest litigation (PIL) filed by ‘Vishwa Bhadra Pujari Purohit Mahasangh’ has sought directions from the apex court to declare Section 4 of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act as “ultra vires”, i.e., beyond legal power or authority and unconstitutional. The PIL brings to the apex court’s notice how the Act has barred citizens from seeking judicial remedy against encroachment of their places of worship by “hoodlums”.

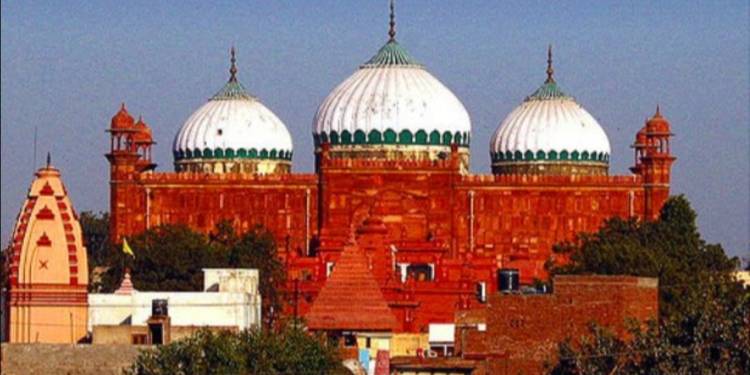

The PIL also states that Parliament has no right to close the doors of the judiciary for aggrieved persons, adding that it cannot take away the powers conferred upon the country’s courts under Article 226 and 32 of the Constitution. If there is constructive action on this PIL by the apex court and the PoWA is indeed rendered toothless, it will pave the way for Hindus to reclaim their major temples which have been destroyed, and over which Mosques have been erected. The Kashi Vishwanath Mandir in Varanasi that was converted into the Gyanvapi Mosque, the Keshavnath temple in Mathura that was converted into Idgah Mosque, the Adinath temple in Malda that was converted into Adina Mosque, the Kali temple in Srinagar that was converted into Khanqah-e-Moula, among others, stand as prime examples of the same medieval plunder.

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 is a Parliamentary law which states that all places of worship, irrespective of religion, shall continue to operate, without hindrance and obstruction, as the exact worship sites which stood on August 15, 1947. By virtue of the same, for example, if a Mosque is built over a temple, and the superimposed structure existed as on 15th August 1947 in its present form, then no action can be taken to change the place of worship’s current form. This means that in presence of this law, the Kashi Viswanath Mandir cannot be reclaimed by Hindus in its entirety because the Gyanvapi Mosque stood over it as on 15th August, 1947. Section 4 (1) of the Act expressly provides, “It is hereby declared that the religious character of a place of worship existing on the 15th day of August, 1947 shall continue to be the same as it existed on that day.” It is this precise clause which the current PIL filed before the SC wishes to nullify.

The Places of Worship Act was brought in 1991, by the then PV Narsimha Rao government, at a time when the Ram Mandir movement was at its peak. Its aim was simple – to be made to appear secular, however, to prevent Hindus from initiating a temple reclamation drive across India. While the Ayodhya dispute was exempted of the same, the other temples were declared out of bounds for Hindus to turn their eyes towards.

The historic Ram Mandir verdict of last year, however, has raised the aspirations of Hindus, who are now keen to get their major temples back. Kashi and Mathura have particularly been in the eyes of Hindus, and it was but expected that post the resolution of the Ram Janmbhoomi dispute, the focus would shift to the other two towns of Uttar Pradesh housing sacred Hindu temples.

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, serves as the biggest roadblock to the same. Unlike in the case of Ayodhya, the presence of a portion of the Kashi Vishwanath Mandir is explicitly visible, and the Gyanvapi Mosque too stands as a memento of Islamic invasions alongside. The only hurdle, however, is the said Act, which is brazenly biased against Hindus. In the absence of this Act, the reclamation and restoration of major Hindu temples will be a cakewalk, unlike the Ram Janmbhoomi case, which was an arduous journey.