Face-offs between the Indian Army and China’s PLA troops along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh have now taken the shape of a tense eyeball-to-eyeball standoff situation.

Comparisons are being made with the Doklam stand-off in 2017, but a careful analysis reveals that the situation here is more serious than the 2017 stand-off. The ongoing tensions in eastern Ladakh could see China and India get involved in a swift, limited theatre armed conflict- one that might be the biggest of all armed confrontations between the two Asian neighbours since the 1967 Nathu La battle.

The reasons for considering the ongoing tensions as more serious than the Doklam stand-off are many. First of all, the recent reports suggest that the stand-off is not limited to one particular spot unlike the 2017 stand-off. According to the Indian Express, the People’s Liberation Army has intruded across three places in the Galwan river area in Ladakh. At each of these three points, 800-1000 Chinese soldiers are said to have crossed into India’s side of the LAC, the effective Sino-India border.

On the other hand, the troops of the two countries are also locked in a tense situation at the Pangong Tso lake, almost 200 kilometres South of the Galwan valley area. This gives an idea of the broad range of eastern Ladakh which is currently mired in tensions.

The Chinese intrusion itself is unprecedented because the LAC in Galwan valley corresponds to China’s official claim line. Therefore, the Chinese troops are intruding into the Indian territory even as per Beijing’s perception of the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Secondly, the face-offs here are more intense than they were in Doklam before the 73-day stand-off situation developed in 2017. Sources told ANI, “The behaviour of the Chinese has been like the Pakistan-backed stone-pelters who use stones and sticks to target Indian security forces in the Kashmir valley. The Chinese troops came armed with sticks, clubs with barbed wires and stones in an area near the Pangong Tso lake during a face-off with Indian troops there.”

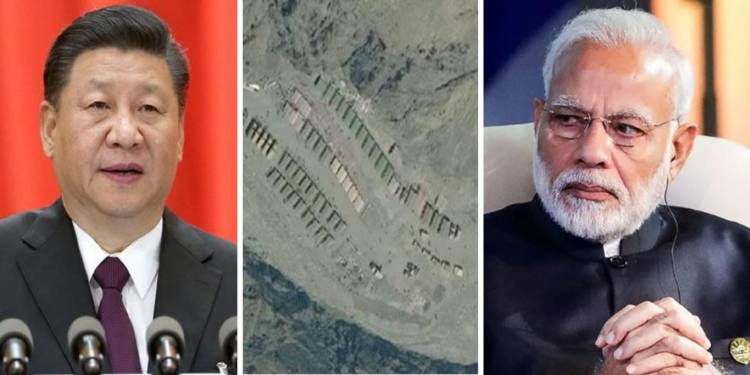

Sources also hint larger numbers during the face-off as the Chinese troops arrived like “locust swarms”. An India Today report has revealed satellite images which show tents, trucks and earth-moving machinery in the Galwan river valley.

Thirdly, the local border mechanisms have failed to defuse tensions that creates a peculiar situation. According to sources, several rounds of “hotline talks” and Brigadier-level negotiations have taken place but there are no signs of disengagement yet.

And it is safe to say that tensions are not getting defused because the stakes are high- Beijing’s growing concerns over the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Gilgit-Baltistan have set the tone for increased Chinese activity in Ladakh.

CPEC is too big a project for China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as it helps Beijing reach the Gwadar port in Pakistan. This holds strategic importance for the Dragon as it helps it to bypass the Strait of Malacca- the main shipping lane between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean which is currently dominated by the United States.

China’s concerns are fuelled by India’s growing ambitions and assertiveness in the region. Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan both of which happen to be Indian territories occupied by China and Pakistan respectively happen to be de jure Indian territories.

Beijing raised the issue of Article 370 abrogation at the UNSC three times at Pakistan’s behest. But what Beijing is also worried about is the emboldened character of India, wherein New Delhi is vocal about its legitimate claims on Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan. India has been claiming its territory in a far more assertive manner post-Article 370 abrogation. If India succeeds, China would lose the CPEC which Beijing expressly agrees to be a pivotal part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

At the ground level, the PLA sees red in some solid road infrastructure that India has built near the LAC. The new roads connect India to the LAC, or in fact run along the alignment of the LAC in these areas.

And then what is happening in Ladakh could be a result of what is happening beyond Ladakh. China is disillusioned by India’s particularly assertive behaviour on international issues concerning China. India has started to take a stand on different issues- signing an EU-drafted document for investigation into the zoonotic origins of the Coronavirus and somewhat tilting in favour of Taiwan’s pro-Independence leadership. To irk the Dragon further, India is also accelerating the exodus of foreign companies from China.

China is trying to warn India against taking such a bold stance through border clashes. But India isn’t backing off, while China cannot afford to disengage- the country got a bloody nose during the Doklam stand-off and the PLA cannot afford another embarrassment.

China wants top-level politico-diplomatic intervention from India’s side, but India is not even a pale shadow of the timid player that it used to be. At the root of the skirmishes is India’s growing ambitions and assertiveness. China wants to cut India to size, while the latter is not backing off. This is why the Ladakh stalemate might not end any time soon, and we might as well witness the biggest short-term armed confrontation since 1967.