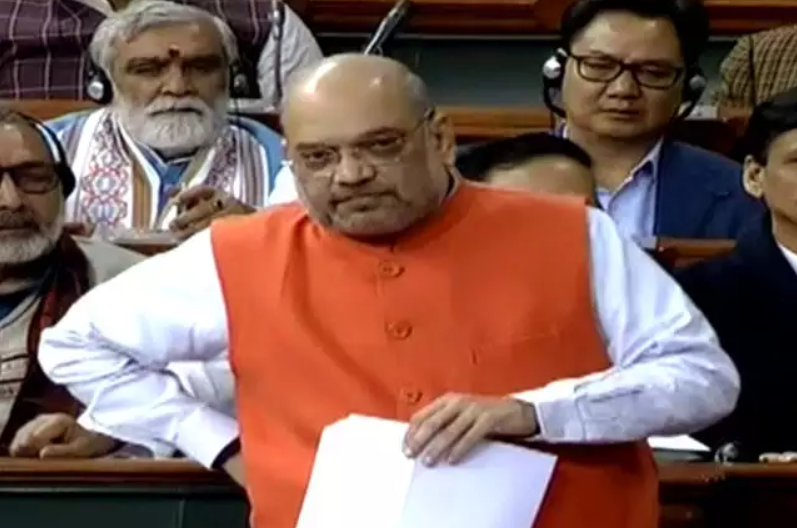

Following a heated debate, the Lok Sabha passed the Citizenship Amendment Bill 311-80 at midnight. This Bill seeks to pave the way for Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians who come from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan facing persecution there to be treated as Indian citizens rather than being treated as illegal immigrants.

The Hindu community forms the bulk of the minority in Pakistan and Bangladesh where they have been facing violence and religious persecution since 1947 when India was divided on communal lines. This Bill, therefore, seeks to correct the historical injustice meted out to the minority communities, including the Hindu community, in India’s neighbouring countries- Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

While the Bill faced severe criticism from the pseudo-seculars and the opposition, there is a need to analyse why India needs the Citizenship Amendment Bill to protect the Hindus of India’s three neighbouring countries. Taking the case of Pakistan first, the country is officially called the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Article 2 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan explicitly declares, “Islam shall be the State religion of Pakistan.” Therefore, Hindus in Pakistan become second class citizens straightaway.

Hindus have faced harsh discrimination and violence in the terrorist country ever since Pakistan’s inception. The country has witnessed a huge demographic alternation over the last seven decades. There were 47 lakh Hindus in Pakistan in 1947 at the time of partition constituting 12.9 per cent of Pakistan’s population. Today, Hindus are said to constitute just a little more than 2 per cent of Pakistan’s total population. Now, where did the Hindus disappear? Some of them came to India, others were converted and many of them were killed within Pakistan. In Pakistan, Hindu persecution has become an almost accepted norm. News cycle is filled with stories of abduction, murder, rape of Hindus in the country. A similar incident happened last year in the Sindh province where a young Hindu girl, Ravita Meghwar was forcibly converted and married to a Muslim man. Now, if they seek citizenship in India citing religious persecution that they continue to face in Pakistan, then it would be a grave miscarriage of justice to deny them the only means of escaping persecution at the hands of an Islamist regime.

The case of Bangladesh also marks a stark resemblance to the case of Pakistan. At the time of partition, Hindus constituted about a third of the then East Pakistan’s (now Bangladesh) total population. Today, Hindus constitute around 8 per cent of Bangladesh’s total population. Though established as a secular country after its independence in 1971, Bangladesh has recognised Islam as the state religion again highlighting the issue of second-class treatment of Hindus in the country. What ought to be mentioned here is that the case of Bengali Hindus migrating into India after facing persecution in Bangladesh is peculiar in the sense that while for Punjab, the partition meant an instant exchange of population, there was no such instant transfer of Bengali Hindus living in Bangladesh to India. Their influx into India continued for many years after partition. This gradual process was further complicated by the illegal immigration from Bangladesh out of social and economic reasons, which took place alongside the migration owing to religious persecution. There is a need to differentiate between those who came to India fleeing religious persecution and those who come to India from Bangladesh out of social and economic compulsions.

The very notion that the exodus of Bengali Hindus into India was temporary and that they would ultimately go back to their original homes, that is Bangladesh, only worsened the situation. This misconception stemmed out of the Nehru-Liaquat Pact of 1950 and our policymakers lived in this illusion till 1972. The official neglect too arose out of this illusion. There was no effort put on initiating rehabilitation programmes for the Bengali Hindu refugees and other communities fleeing persecution in Bangladesh. In fact, they have not even been considered as Indian citizens. Now, the Citizenship Amendment Bill seeks to correct this historical anomaly.

Not much needs to be said about Afghanistan. Article 2 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan declared Islam as the State religion. However, a bigger problem is posed by the dominance of Taliban in the country, which continues to control over 60 per cent of Afghanistan’s territory. It is relevant to mention here that in the year 2001, there were reports about Hindus being forced to wear ‘badges’ in Afghanistan by Taliban so that they could be identified separately, a practice that was reminiscent of the yellow star of David that Jews were compelled to wear in Nazi Germany. This gives an insight into the kind of violence and harassment that the Hindus in Afghanistan must be facing at the hands of the Taliban in India’s neighbouring country.

The fact remains that minorities, predominantly Hindus continue to face large-scale violence in these countries and as such, they have no other country but India to look up to. When it comes to Pakistan and Bangladesh, the reality that India was divided on religious lines must be accepted, and once this reality is accepted there is no cogent reason why Hindus in Pakistan and Bangladesh must be made to suffer at the hands of Islamism in the two countries. A look at the history of atrocities of Hindu minorities in neighbouring Pakistan and Bangladesh sends a chill down the spine and makes a compelling argument for the Citizenship Amendment Bill. The reality of Hindus’ continued persecution in these countries is the reason why India needs the Citizenship Amendment Bill to protect them.