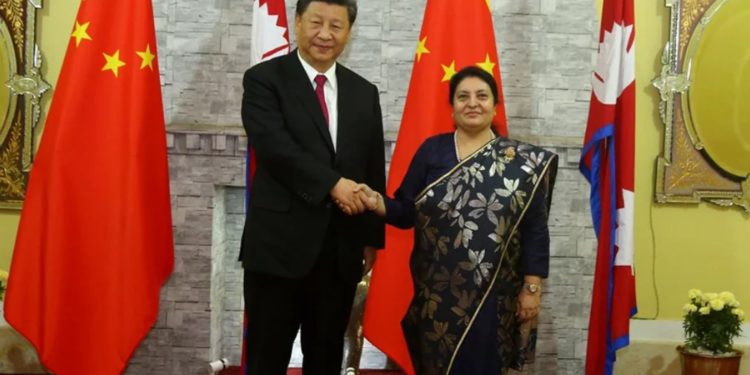

Chinese President Xi Jinping has become the first Chinese President in 23 years to visit the landlocked Himalayan country. The two countries have reportedly signed 20 deals and in what illustrates China’s growing influence over Nepal, the Dragon has also extended financial aid of $500 million. With this, Nepal might have become the next victim of China’s debt trap.

The Communist regime in Nepal seems to have paved the way for China to increase its influence in the Himalayan country. Nepal’s Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali said, “Our priority is to create opportunities for Nepal, joining it to China’s development. We are focusing on connectivity between the two countries.”

The Communist government in Kathmandu is eager to forge closer ties with China. However, it doesn’t realise that it could also end up falling prey to China’s debt trap that has already claimed victims such as Sri Lanka and Maldives.

Sri Lanka’s case is a glaring example of how Chinese financial assistance can prove detrimental to national interests. During the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime, Sri Lanka had made an open request for funding of the Hambantota port. China was the only country to respond and the Export-Import Bank of China provided a US $ 307 million loan to the island country at an exorbitant interest rate of 6.3 percent. Despite the port turning out to be a failure and performing rather poorly, China kept investing in the port.

The Sri Lankan government ended up in a huge debt crisis and reached a situation where 90 percent of its revenue was going towards servicing debt. In order to ease the burden of mounting debt, the Sri Lankan government handed over 70 percent ownership of the port through a 99-year lease to the China Merchants Group, a state-owned Chinese company. The ‘Hambantota’ effect, therefore, narrates the grim tale of how Chinese financial aid can bring in a huge debt crisis and it is primarily the reason why regional players must remain cautious of the Dragon’s ostensible benevolence.

In 2017, Nepal also joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI has already led to concerns about how China’s flagship trans-national infrastructure project could create a huge debt crisis for the underdeveloped countries which will form a part of the BRI initiative. The cost of the massive project is estimated to be $1 trillion. While China claims that the initiative is a big opportunity for the regional players to revitalize their economies, the fact remains that China does not give grants to those joining the BRI rather it extends loans at commercial rates.

Now, it is being seen as an imminent threat that could end up leaving many such countries with unsustainable debt. This would once again push these countries towards the ‘Hambantota Effect’. Take the case of Laos, for example, where China is funding a high-speed rail project that costs half the country’s GDP. This, therefore, does not seem like a benevolent attempt at empowering Laos but more like a strategic financial aid that would leave such countries reeling under impossible debt burden. The island nation of Maldives is also burdened with a whopping $3.4 Billion debt to China, however, a regime change in the country last year, dethroning pro-China leader Abdulla Yameen signalled that Maldives seeks to rectify its debts.

Nepal has unfortunately embarked on the process of falling into this debt trap in the garb of infrastructure development under the BRI. The landlocked country jumped into being a part of the BRI in 2017. China is going to fund the trans-Himalayan rail line and other infrastructure projects. Nepal and China have not yet arrived on an understanding as to the mode of funding for the BRI projects, that is, whether they will be in the forms of loans with commercial rates of interest or grants that don’t have to be paid back. Nepal has been seeking grants to build the Trans-Himalayan railway.

However, with the Oli regime warming up to the Dragon, it is highly likely that Nepal might not insist on grants as a pre-condition for starting construction on these infrastructure projects. There are concerns in Kathmandu about the project turning out to be technically and financially infeasible or a White Elephant for the landlocked country, even if completed successfully. If that were to happen, the trans-Himalayan Railway would prove to be Nepal’s Hambantota moment. Nepal has certainly started moving towards the risk zone with a Communist regime at the helm of affairs. The Himalayan country must tread cautiously lest it should fall into the same Chinese debt trap as Sri Lanka and other such countries.