Perhaps for the first time since the anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu in the 60s, the language issue has come to the fore in the Indian politics once again. There are voices critical of the imposition of Hindi in the Southern states, most recently in Bengaluru, where the prominence accorded to Hindi at Namma Metro signages aroused some ire. While there may be truth to the fact that Siddharamaiah led Congress government is playing dirty tricks (another example being the Lingayats’ demand for a separate religious status) to prevent its inevitable downfall at the hands of the BJP, it is equally true that language, even 7 decades after independence continues to be a highly emotive and divisive issue. Supporters of Hindi as a national language point to the fact that it is the most widely spoken national language.

The retort to which is the quote by Annadurai that if one were to go by numbers, it would be the common crow and not the majestic peacock that would be the national bird. Many states fear, and perhaps not unreasonably that Hindi would eliminate all local languages just as it has subsumed Rajasthani, Haryanvi, Braj Boli, Chattisgarhi and others. They contend that instead of imposing Hindi, one should let English continue as the lingua franca, even though English’s track record of annihilating native tongues is much worse. But in this English vs Hindi debate one tends to overlook the importance of regional languages in a nation as wide as India.

After all, isn’t it impossible to imagine an India where a Bengali disowns his mellifluous Bangla bhasha, where a Maharashtrian forsakes Tukaram’s Ovis, where the softness of Axomiya is forgotten and where the love behind a Haryanvi’s harsh tones is unappreciated. After all what is India, if not for Telugu, Tamil, Malyalee, Kashmiri, Sindhi, Gujarati and countless other languages and their dialects. After all, isn’t India the land where “kos kos par badle paani,chaar kos par vaani”

One reason why the language issue evokes so much passion is because of the recent experiences. Cities such as Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune etc., unlike Mumbai and Delhi perhaps have always had a thriving regional culture. These cities have in their own right been torchbearers of that culture. With the IT boom, these cities underwent a drastic transformation.

Non-native populations flooded these cities. These immigrants seemed unwilling to imbibe the culture of the places where they had set up home. In Bengaluru for instance, they made no efforts to learn Kannada, enjoy the local cuisine, partake in local festivals and rituals. They remained like the old British sahibs, living in yet distant from India. While some did make an effort to acculturate themselves to the new environment, most remained unwilling to adapt themselves in the new environment.

There are people who having stayed in Bengaluru for decades would still know nothing about Kannada language other than “Kannada Gottilla”.

Similarly in Pune, where the Marathi manoos already struggling for an identity in Mumbai, now finds himself sidelined in Pune. While Raj Thackrey’s diktat demanding Marathi movies to be shown in prime time in theatres might be an extreme, it was necessitated by the onslaught of Hindi centric Bollywood on Marathi film industry.

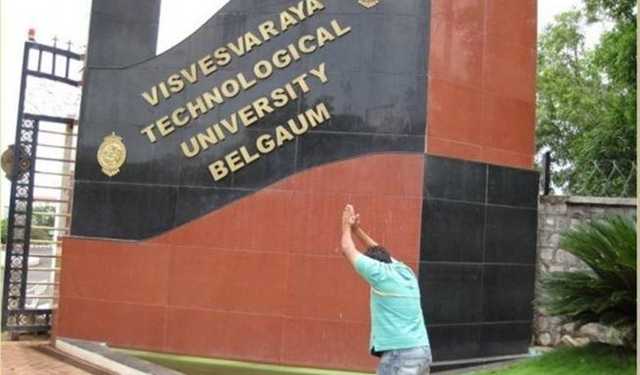

Such cases need not have occured if non-natives made some effort to learn the culture and language of the place they were calling home. PM Narendra Modi hit the nail on the head when he said people should feel as much pride in knowing language of another state as they do when they learn a foreign language. Or even when he talked of student exchange programmes to help them understand India’s culture better. Karnataka’s Visvesvaraya Technological University has proposed a practical way of putting this vision into a practical reality. As per news reports, the University has proposed that students of first and second semester must compulsorily learn Kannada and clear language tests. For the lakhs of Non-Kannada speaking students who enter Karnataka every year for further studies, this is an excellent opportunity to pick up the language of the state where they would spend the next 3-4 years or perhaps even the rest of their lives. This effort can easily be replicated across the nation. Universities in Gujarat could make elementary Gujarati compulsory for all students in the first year of college education. Imagine the joy for a Tamilian when a “North Indian” would converse with him/her in Tamil.

Politics aside, our native languages are dying. More parents than ever before and encouraging their students to learn and converse in English. In a matter of a generation or two, India would have a substantial number of people who would call English their mother tongue. Imagine the disservice that this would do to our common, shared cultural heritage. Attempts, such as the one made by VTU need to be applauded and not looked at through narrow lens of language hegemony. Imagine an India where a Malayalee speaker would be as fluent in Hindi as in Odiya. Imagine for a second that a Maithili speaker would win a Sahitya Akademi award for his work in Tamizh language. Wouldn’t that be an India one will be proud of?