“I would have fired with machine guns, if I could.” – Dyer, November 19, 1919.

The Hunter Commission, comprising of 7 people, 4 British and 3 Indians, had reached a consensus among themselves regarding the actions of General Dyer. Sir Setalvad, Vice Chancellor of Mumbai University, was one of those 7. This is an extract from that conversation:

Setalvad: “Is this right that you had taken 2 armoured vehicles with you?”

Dyer: “Yes.”

Setalvad: ‘To my knowledge those cars did have machine guns mounted?’

Dyer: “That is correct.”

Setalvad: “When you took the vehicles along did you mean to have the machine guns used at the crowd?”

Dyer: “If necessary. In case I was attacked, or anything else in similarity, I presume I would have used them.”

Setalvad: “When you arrived at the scene you were not able to take the machine gun mounted cars inside because the corridor leading up to the garden was too narrow?”

Dyer: “That shall be a yes.”

Setalvad: “Supposedly, the passage was wide enough to let you take the cars with mounted machine guns, would you open fire with those guns?”

Dyer: ‘I think, yes.’

April 13, 1919.

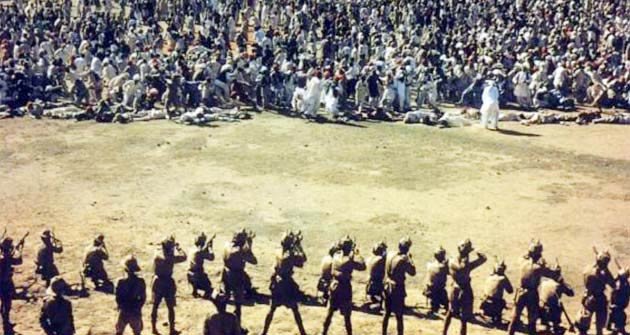

A non violent crowd had gathered from places around Amritsar who were unaware of the curfew in effect, after the civil unrest. Colonel Dyer (he was a temporary Brigadier General, even though popular as General Dyer), with his 50 men surrounded the only major exit in the Jallianwala Bagh, a field enclosed by walls from all sides.

He opened fire, with possible planning from the then Governor of Punjab, Michael O’Dwyer, on the unarmed crowd of 26000 people including women and children who had reached the city to celebrate Baisakhi, a festival which will still be of the colour red, after 98 years.

The British figure stated 379 dead and 1100 wounded, however an estimated number is well above 1500, upto 2000 and could be further more. 200 bodies were pulled up from the well itself, in which the people had jumped in to save themselves. As many people died of bullets, much more died of stampede. In later accounts, it was revealed that Dyer until all the ammunition had gotten over.

Baisakhi turned into a bloodbath. The bullet holes are still visible today.

The entire story took a while to break out across the country. People were appalled. The Moderates like Gandhi, the intellectuals like Rabindranath Tagore had to eventually, unwillingly wake up from their dream, where the Britishers were able administrators, and that “ardh-swarajya” (or the reforms like Montague-Chelmsford) would be a tremendous achievement.

Gandhi returned his ‘Kasar-i-Hind’ medal while Rabindranath Tagore returned his knighthood, but what difference would it create in a country which was being humiliated and made to bleed on a daily basis?

The intellectuals, who went to the Britain’s for more premium education, had always been soft regarding the British. With riches and reputation, why would they step off their carriages and look onto the street full of starving children?

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of innocent people forced their head in the direction of reality.

The Early Nationalists were forced to realize that begging would bring no difference from a government whose only purpose was profit, which considered itself a superior race, and morally obligated to teach the Indians the ways of a civilized human, in words of Churchill himself.

But still, the Early Nationalists would not resort to stronger means. In Dec 1919 after 8 months of the massacre, a resolution of loyalty to the emperor and of satisfaction on successful termination of War was passed by the Indian National Congress. Interestingly, Mahatma Gandhi was at the helm of most affairs of Congress, at the time. This moment could have been used to declare an all out non violent non cooperation movement as the public was enraged, but it was wasted in bootlicking.

As for Dyer, he was asked to return to England, which when he did, was hailed as a hero and savior of the British Empire. Winston Churchill, in his speech in the house of commons, did declare his act monstrous, but also deemed it necessary.

He was applauded in the House of Lords. (Yes, for killing unarmed women and children). The conservative newspaper Morning Star started a fund in his honour much before he set foot in England. Rudyard Kipling, the famous English author with stories based on India, supported him in no less than 4 places after the massacre. A few British Indian newspapers became a part in the fund-raising too — the Calcutta Statesman, the Madras Mail, the Englishman etc. He was handed 26,000£ from fund raising (quite a lot when converted to today’s money) on his return by the Morning Star for his marvelous work in Amritsar. He held the Colonel designation until he died in 1927. But the man pulling the strings from behind, the Governor of Punjab who let all of this happen under his rule, was Michael O’Dwyer. He was a clear supporter of Dyer ’s actions of terrorising the civilians to stay in power. However, he shifted the blame on others soon.

Udham Singh, a man of deep seated courage and obligation towards his country, who stood witness to the brutal massacre at Amritsar, waited patiently on his seat at Caxton Hall. Michael O’Dwyer, the silent supporter and motivator of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre was about to speak. As soon as he approached the podium, Udham Singh emerged from the audience and shot him twice, in the chest. O’Dwyer died on the spot. It was not mere vengeance, angst, or insanity, which Gandhi termed it as.

The real planner of the massacre, the perpetrator, the racist humiliator were all the same person: Michael O’Dwyer. And he was an honoured gentleman here in Britain. For him, the massacre was nothing more than a small event to save the British Raj, as state terror will firmly ensure the government is in the hands of the superior race.

Millions of Indians were racially hounded everyday by the Britishers, who could barely be called humans in today’s society. But the man who yelled “FIRE!” at the face of women and children, was honored, was called a savior, died a free man. The man who supported, probably put the idea into execution, O’Dwyer, walked free and honoured. His entire existence was a spit in the face of humanity.

The entire British race, with its arrogance of racial superiority was nothing short of a blot on the entire human history. We must never forget any injustice done to anyone, and here the mass murderer of our people, was applauded for his job.

Where was justice and equality when this happened? Non-violence could never be achieved in an unjust system, but yes, a message could be sent, to not just the British and to the Indians, but to the entire world that the inhumane racist acts will have no place in our society, and if perpetrated, they can be reciprocated with similar inhuman acts.

British Prime Minister David Cameron on his visit India, laid a wreath at Jallianwala Bagh, and is quoted to have said, “the most shameful event in British History.”