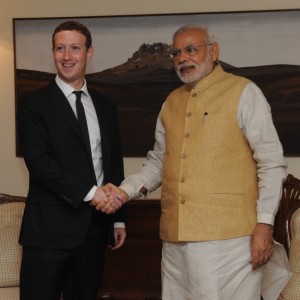

As faculty who engage South Asia in our research and teaching, we write to express our concerns about the uncritical fanfare being generated over Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Silicon Valley to promote ‘Digital India’ on September 27, 2015.

Firstly, many who have signed this letter not only engage South Asia in their research and teaching. They appear to be of South Asian descent too. Why they would mind the ‘uncritical fanfare’ this visit is generating baffles me. After all, this is the elected leader of the land in which they were born and brought up. But let us leave that aside. There isn’t a single instance of ‘uncritical fanfare’ that was generated. The premise of the letter is hollow.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Silicon Valley highlights the role of a country that has contributed much to the growth and development of Silicon Valley industries, and builds on this legacy in extending American business collaboration and partnerships with India. However Indian entrepreneurial success also brings with it key responsibilities and obligations with regard to the forms of e-governance envisioned by ‘Digital India’.

This paragraph seems redundant. I wouldn’t expect a group of NRI academics trying to put forth an argument to fit something as unnecessary and obvious as this into the letter. But they reserve their right to do so.

We are concerned that the project’s potential for increased transparency in bureaucratic dealings with people is threatened by its lack of safeguards about privacy of information, and thus its potential for abuse. As it stands, ‘Digital India’ seems to ignore key questions raised in India by critics concerned about the collection of personal information and the near certainty that such digital systems will be used to enhance surveillance and repress the constitutionally-protected rights of citizens. These issues are being discussed energetically in public in India and abroad. Those who live and work in Silicon Valley have a particular responsibility to demand that the government of India factor these critical concerns into its planning for digital futures.

No doubt it is a legitimate concern. After living in the U.S. for years, it is nice to see them distressed about surveillance. They seem unperturbed by what’s being perpetrated at home, but very bothered about a POTENTIAL similarity elsewhere. Whether this is pure selflessness or blissful ignorance or sheer stupidity, is anyone’s guess. And without getting into the merits and demerits of surveillance, those who live and work in the Silicon Valley have aided American agencies with this endeavour. Whether they did it on principle or against their wishes doesn’t discount the fact that it happened. So essentially the NRI academics are asking them to treat the Indian government differently from the American government. I won’t insinuate further, but that is a dangerous path to tread on.

We acknowledge that Narendra Modi, as Prime Minister of a country that has contributed much to the growth and development of Silicon Valley industries, has the right to visit the United States, and to seek American business collaboration and partnerships with India. However, as educators who pay particular attention to history, we remind Mr. Modi’s audiences of the powerful reasons for him being denied the right to enter the U.S. from 2005-2014, for there is still an active case in Indian courts that questions his role in the Gujarat violence of 2002 when 1,000 died. Modi’s first year in office as the Prime Minister of India includes well-publicized episodes of censorship and harassment of those critical of his policies, bans and restrictions on NGOs leading to a constriction of the space of civic engagement, ongoing violations of religious freedom, and a steady impingement on the independence of the judiciary.

Their acknowledgement, although it has no bearing whatsoever, means a lot to all of us. However they don’t sound like ‘educators who pay particular attention to history’ but instead ‘educators who pay attention to particular history’. Whatever the reasons for his being denied the right to enter America, the U.S. administration was made a monkey of when the world’s biggest democracy decisively elected him. All their surveillance inputs seemed to have failed them. They hastily rolled out the red carpet for him, and Mr. Modi obliged magnanimously. Obviously this does not absolve him IF he were responsible for the atrocities the NRI academics attribute to him. But they used the words ‘powerful reasons’. It is clear now that the U.S. administration had no conviction in those reasons. Mr. Modi has often been accused of playing a role in the Gujarat violence of 2002. However these allegations were unsubstantiated from the beginning and several courts have acquitted him already. Through the years, it has become increasingly clear that the accusations against him were false. They were made with ulterior motives in all probability. Modi’s first year as Prime Minister has been successful and he still remains highly popular. Contrary to the claims that people who are critical of his policies are harassed, he has been a victim of such people. An uncooperative opposition and several civil agitations have impeded his agenda of development. Only non-governmental organisations who have refused to disclose their sources of income have been banned and rightly so. If these sources are legitimate, if the money coming in isn’t supposed to be used to destabilise the country, I see no reason why this secrecy should prevail. There have been no instances of violations of religious freedom, or any sign to suggest an impingement on the independence of the judiciary.

Under Mr Modi’s tenure as Prime Minister, academic freedom is also at risk: foreign scholars have been denied entry to India to attend international conferences, there has been interference with the governance of top Indian universities and academic institutions such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, the Indian Institutes of Technology and Nalanda University; as well as underqualified or incompetent key appointments made to the Indian Council of Historical Research, the Film and Television Institute of India, and the National Book Trust. A proposed bill to bring the Indian Institutes of Management under direct control of government is also worrisome. These alarming trends require that we, as educators, remain vigilant not only about modes of e-governance in India but about the political future of the country.

If it is true that foreign scholars have been denied entry to India for reasons that concern India directly, well and good. If on the other hand they have been denied entry on the whims of those at the helm affairs with no substantial basis, remember that this is usual government practice. Mr. Modi himself was a victim of this phenomenon for nine years, as the NRI academics themselves pointed out earlier. Interference or underqualified appointments in several institutions are also unsubstantiated allegations. These surface only when persons overtly sympathetic to the previous regime are replaced. And as for the academics’ charge of incompetence, it is an absurd assumption to make without any data whatsoever. It is true that students of some educational institutions have protested against the government’s moves but being a student myself, I know how easy it is for students to become disgruntled. I come from a town called Pondicherry, and the Pondicherry University was one such institution. I have friends who study there and I came to know from them that their concerns were legitimate and they have been taken care of. This impression that the government is creating impasses instead of resolving them is untrue. The academics who write this might be South Asia experts, but every Indian who actually lives in India knows that there is no threat to the country’s political future.

We urge those who lead Silicon Valley technology enterprises to be mindful of not violating their own codes of corporate responsibility when conducting business with a government which has, on several occasions already, demonstrated its disregard for human rights and civil liberties, as well as the autonomy of educational and cultural institutions.

Every false and senseless notion mentioned in the concluding paragraph has been dealt with already. The letter in its entirety looks like a political speech: flowery, baseless and not befitting the NRI academics. It is natural that people who live in India are more in touch with its present day reality than those who do not. But for a group of NRI academics who claim to ‘engage South Asia in our research and teaching’, the extent of misconstruction shocks me.

I can list out the government’s achievements in the last one year, recent election results and surveys to back my disagreement with this letter. But its stubborn condescension and blatant inaccuracies lead me to suspect that its authors do not care about the response it generates. It leads me to suspect that there are ulterior motives behind the letter, that it is the creation of a larger Modi-baiting machinery or an attempt by some NRIs to grab the limelight back home. Letters of this kind begin to gather dust in a matter of days, and this one will be no exception. But the ability of fellow Indians sitting abroad to even attempt something that might adversely affect my country disappoints me.