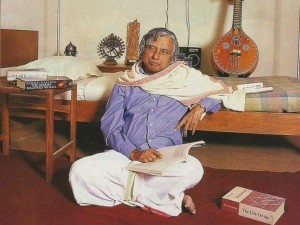

Among the most revered of Indians was A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who left us on the 27th of July. Eminent personalities and common men alike expressed their solidarity and paid their condolences. The internet, television and streets were filled with his pictures and quotes. His demise united the country. Nobody in India has risen to such political heights without being disliked by a single section of society. But certain voices did surprise us with their distasteful and wrong ideas about the man, both during and after his lifetime.

The most prominent one was Abdul Qadeer Khan. Khan was considered to be Kalam’s Pakistani counterpart by many. He is supposed to have founded Pakistan’s uranium enrichment programme for its integrated atomic bomb project. Khan said of Kalam after his death that the latter had been ‘an ordinary scientist’. It is hard to believe that the man was unaware of Kalam’s credentials- Kalam is known as India’s Missile Man for his work on developing ballistic missiles and launch vehicle technology. His role, organisational, technical and political, was by far the most important in India’s Pokhran Two nuclear tests of 1998. But around the same time that Kalam was India’s president and the most loved one that too, Khan languished under house arrest in Pakistan. His dealings with other countries were under the scanner, and considering who he was, these dealing were very dangerous for Pakistan. Khan never received the love Kalam received from his countrymen. Khan never made it to the presidency of his country. So it is fair to say that Khan’s remarks were a case of sour grapes.

One of Kalam’s earlier detractors just after he became president, was Sagarika Ghose. She wrote an article in the Hindustan Times titled ‘Science is tough’, which has gone viral after Kalam’s passing. Ghose referred to Kalam as Bomb Daddy and just stopped short of calling him an RSS agent. She also asked him to heed Nehru’s words of not letting science divorce morality for then it may be used for evil purposes. The feeling many got after (re)reading that article was that journalism had divorced morality and was being used for evil purposes. One can identify pseudo-secularism when the most magnanimous of gestures is twistedly projected. Here, poor Kalam became a victim of another’s ulterior motives.

After his demise some other articles denouncing Kalam also emerged but they seemed to be written by unknown people who sought attention. We don’t intend on answering such rubbish and giving them the last laugh.

One article that went viral after Kalam’s demise was about how he averted the ‘Hindu Bomb’ tag. According to it, the major role that he played in India’s nuclear program is the only reason India’s nuke isn’t known as the Hindu Bomb. It would have been interesting to see Kalam react to such a hypothesis.

The fact is that after Pokhran Two, we saw sanctions come and we saw sanctions go. The West did whatever it had to do, and so it would make no difference to India whether they called our nuke the Hindu Bomb or not. It all comes down to how we ourselves would have perceived that nuke. The very notion of Hindu Bomb exists only because Pakistan’s nuke is known as the Islamic Bomb. But we are a secular country unlike Pakistan. Kalam would have called it the Indian Bomb and not the Hindu Bomb irrespective of whether he worked on it or not.

Kalam’s death was compared to another death that took place around the same time, a state sponsored killing as some obnoxiously called it. This was done purely on a religious basis. On social media, many told the Muslims that they could either go the Kalam way or the Memon way, and that the choice was theirs. With a hundred and eighty million Muslims in India of which most have been living in peace, it is unfair to use Kalam’s demise to send out such a hastily generalised message. As our prime minister says, “Indian Muslims will live for India and die for India.”

But this isn’t about Indian Muslims, Hindus or Christians. It is about all Indians living and dying for India. It is about all Indians going beyond caste, creed and race for India’s sake. This is the idea that Kalam was a proponent of. This was his philosophy and his religion. Going the Kalam way of nationalism or the Memon way of divisiveness is a choice that doesn’t lie before a particular community, but before every Indian. Are we prepared to let our identities take a backseat in national interest? Are we prepared to be Indians first, at all times and in every situation? Are we?