A historical primer:

The year 1975 saw the imposition of Emergency, a highly unpopular decision of the then Congress Govt. that was criticized by many as being contrarian to democratic principles. A non-violent, mass movement led by a grassroots leader in the grand GandhiAam Aadmi Party an tradition became the pulse of the nation, culminating into general elections in 1977, that saw a non-Congress alliance comprising of people across the social and economic spectrum (Left vs. Right) winning for the very first time with an absolute majority. The grassroots leader declined to join the Government, but his chosen candidate indeed became the Prime Minister. Despite a clear majority, the Government struggled to govern as it was rift with factionalism and strong ideological polarisations making it hard to draw a middle path. Three years and 2 prime ministers later, fresh elections were called, which saw the return of the Congress. The Janata Party fragmented into smaller parties, and for the rest of its existence was a player that only existed to make the numbers, finally ending its existence by merging with the BJP a few months before the 2014 Lok Sabha elections.

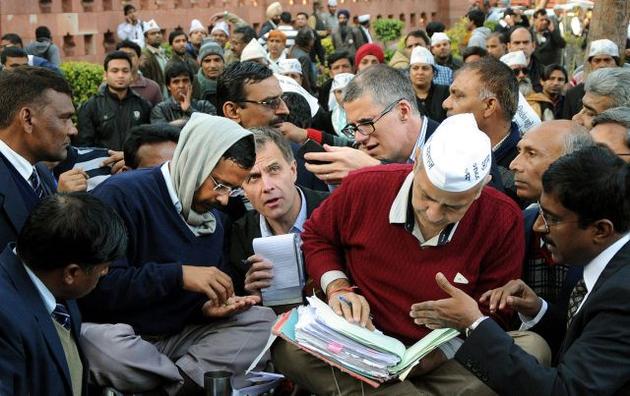

Cut to the year 2011 and the Jan Lokpal movement. Corruption was at the forefront of the public mindspace thanks to the Big 3: 2G, Coalgate and CWG. The scams were criticized by many as being summarily contrarian to the ideas of a free and fair society. A non-violent, mass movement led by a grassroots leader in the grand Gandhian tradition became the pulse of the nation, finally culminating in the elections of a city-state that saw a ‘non-traditional’ party winning an absolute, nay, brutal majority for the first time. The grassroots leader was in no form going to join the Government as he had found the idea of contesting elections unpalatable, paving the way automatically for his chosen one to become the Chief Minister. Despite a clear majority, the Government struggles to govern as it was, and still is, rift with factionalism and strong ideological polarisations. The future is a question mark. This is the story of the Aam Aadmi Party as we know it, a story that is so constantly in flux that it gets harder to keep up with all the developments with time than even Game of Thrones.

While the details may differ, qualitatively the two scenarios described above are very similar and point to an intrinsic cyclical quality to Indian electoral politics. It must be stated right at the start though, that the civil movements that led to the eventual formation of these two parties have no real moral equivalence. The emergency was a fight for the protection of fundamental rights, while the Jan Lokpal movement was an attempt to provide an institutionalised solution to the complex and at times nebulous idea of corruption. The scales are also quite different, namely, the Janata Party governed the Union while the Aam Aadmi Party governs Delhi, a city-state with complex power sharing agreements. Despite these caveats, it is still quite instructive to consider the similarities and differences between the two parties post their inception.

Two sides of a coin?:

The Janata party was essentially a conglomerate of disparate parties across the political spectrum, united under the common banner of anti-Congressism. The Aam Aadmi Party while a singular entity, consisted of individuals across the socio-economic divide united under the common banner of anti-corruption. Both parties also suffered from considerable infighting and had governance issues, despite enjoying a clear majority. The reason for this is painfully obvious. Both parties lacked any form of ideological unity, and their mere existence was based on singular objectives, a one-trick Pony if you will. Such an arrangement is a disaster waiting to happen, as it is unsustainable in the long run. Indeed, the Janata Party could not even complete a full-term and was forced to call for mid-term elections. Whether the AAP could suffer a similar fate is open to speculation, but this author for one believes that it is highly unlikely. While both parties suffered from ideological incongruities, the timing of when it started overriding the common objective is a key discriminant. The ideological fissures in the Janata Party came to the fore only after the 1977 elections, and an year into the Morarji Desai Govt., making it too late to resolve these differences and provide for a reasonable standard of governance. The Janata Party was not lucky enough to get a ‘trial run’ like the AAP, which flirted with governance briefly, retreated into the shadows, coalesced their ideology into something tangible and singular, and reemerged in 2015 as a left-of-centre (or left-of-left, if you are so inclined), populist, and ostensibly secular alternative in the National Capital. The handling of ideological dissidents within the party is also a key point here. The relatively more democratic Janata Party under Morarji Desai for example, tried its best to curb its dissidents on board, to the point of manufacturing their own Cola in order to maintain an economic policy that was in line with the expectations of its left-wing partners. The AAP on the other hand has no such issues, as most of its dissidents have already quit the party under questionable circumstances; circumstances that seem to get murkier by the day and the party functions largely on the whims of a single person and his acolytes.

Political Balkanisation:

Post Indira Gandhi’s re-election in 1980, major components of the Janata Party fragmented into smaller pieces, eventually leaving behind a rump party. Whether the Aam Aadmi Party will also see such similar splinters is once again open to speculation, but it can’t be denied that already a few state units within the party are already feeling strait-jacketed by the high command culture that seems to be de Jure in the party as of now. Additionally, the AAP does not have a viable alternative other than Arvind Kejriwal who can marshal the cadre together to keep the party afloat. Contrast this with the BJP for example, which already had well-known faces such as AB Vajpayee and LK Advani from the Jana Sangh days, and could become a credible credible Center-Right party without much trouble despite splintering from the Janata Party.

The question of legacy:

Ultimately, when an entity ceases to exist, the only question that remains is that of legacy. The Janata Party may have been a failed experiment, but its electoral success had one, extremely far-reaching consequence that still echoes today after so many decades; the Indian electorate can and will look beyond the Congress. The Aam Aadmi Party promises, or at least hopes to leave behind such a singular legacy vis-a-vis anti-corruption. Whether they will succeed is questionable, but even if they do, their limited sphere of influence would mean that this legacy of theirs would be a short-lived one and forgotten in a few years.